ROUND ABOUT THIS TIME, 33 YEARS AGO -- Or how I avoided becoming Syd Barrett.

- Cleaners HQ

- Mar 2, 2021

- 6 min read

To continue with the story. In autumn of 1987, after returning from Hamburg, Giles Smith and I made our best efforts to press on with the album which became Town and Country. Unlike the six-week breeze-through of its predecessor Going to England, the new album was mired in delays, equipment problems and questions about production values. By now I was more or less camped-out on the job. I was also helping Captain Sensible with writing his album and doing everything I could to keep it all trundling along. It was the equivalent of sleeping out on the deck of a ship which had no fuel and no destination.

In fact, Giles Smith documents this story very well in his own book Lost In Music. When I'd begun the Cleaners from Venus, we'd been a ramshackle venture with not much more ambition than to make some good records. Now, with a very much slicker Cleaners Mk 2, I'd seen my original aims compromised somewhat. After a slow but steady campaign of attrition, I was now in a 24-track studio, watching my guitar-based songs being comprehensively marinaded in keyboards, drum machines and what I saw as a rather dubious 1980s production sheen.

Next, I would be subtly coerced into doing more live work. I'd already been dragged out of the studio, at the behest of RCA Germany to do the Hamburg gig. I was getting ill, exhausted and I was beginning to lose my objectivity. FInally, there were cash flow problems. Back home in Essex, meanwhile, the place which I'd been caretaking for some years, had had a change of circumstance. All I will say of it, is that my former landlord came home from exile and told me that he and his family now had 'an enhanced lifestyle expectation.' The story ended well and kindly. The interim period, however, which at times was awkward and uncomfortable, coincided with the beginning of the collapse of Cleaners from Venus Mk 2. In February of 1988, while very run-down, I caught flu. It laid me out for weeks. By March, having just about recovered, with no money coming in, and no official address I found myself down to £10.00 in all the world and the prospect of maybe selling my piano.

At 35 years of age, I think it was possibly the lowest I'd fallen so far. In twenty years of almost unbroken employment, having never signed on, I now still had a place to sleep but no permanent postal address. Most of my possessions were stored in a spare room at a kindly gardening customer's house.

Next a bill arrived from the DHSS. It said that I owed them something close to £270 in unpaid Class 2 self-employed contributions. I took the bull by the horns. I cycled into Colchester -- I had no money for a train - and went to their office. The first thing they told me was that I wasn't entitled to any money. I said I didn't want any money, but did they think they could stop asking me for money - since I currently didn't have any. From behind the brick-proof glass, or whatever the DHSS glass is proofed against, the woman invited me into a small office. I sat there and spilled out my sorry story.

I said that I'd been ill, I told them that I'd never claimed anything before. I said I now earned so little that I didn't even owe any Income Tax. I told them that although I could sleep at my partner's place, or when in London, on the studio floor, I didn't actually have a home at this time. I added that since it was now March, soon, the gardening work would come in and now that I was nearly recovered from flu, I'd be able to re-kindle my old gardening round. I also said that my friend (Nel) and I had just become Colchester's first licensed buskers.

To my surprise, the woman and her colleague, who'd just joined us told me that I'd done the right thing coming in. She told me that I wouldn't have to pay this money, or at least not until I was in work again. Even then, she added, she could see from my records that I was otherwise well paid-up. Against everything I'd every heard about DHSS staff, she was sympathetic to my plight. So was her colleague. They were actually being nice to me. I began to fear that I would cry. I'm glad I didn't. Because if it ever starts, it's hard for me to turn the taps off. She then advised me that the best thing I could do to help myself was to allow them to register me as being of No Fixed Abode. It would be simpler, she said and would take every pressure off me until I was well enough to work. Also, I would be entitled to something called Vagrancy Allowance, a thing of which I'd never heard. Vagrancy Allowance was then worth something like £3.75 a day, I'd have to come into Colchester each day in order to claim it, then, on Friday, they'd give me three days allowance for the weekend. I considered it briefly, but said that post-flu, I'd rather not have to cycle into Colchester and back again while it was so cold. I told her I'd be okay, because gardening work would begin in days. I reiterated that I just needed them to stop asking me for money, which I didn't have. She understood this but seemed to think that it was unusual for anyone to turn down money. I thanked them, signed the No Fixed Abode form and cycled back to my partner's place. The next week, Nel and I, having passed an audition to busk in Culver Square, began doing two or three-hour morning busking sessions, Colchester's Culver Square. We were now legal buskers. We'd make £12 or £15 a session each. It was a start. Days later, I began picking up gardening jobs again.

In early April an unexpected royalty cheque worth a few hundred pounds arrived. Then, my music publishing money was restored. Only 3 weeks earlier, I'd been desperate and it had all seemed hopeless: Ten pounds to my name, and trying sell my piano. Now I had work again:gardening and helping a builder friend to replace fences flattened by the October hurricane. Nel and I were busking. I'd paid off my debts and still had a few hundred left in the bank. There was even a bit of good news on my housing situation.

Then, as always, there was a phone call. A 20-city German tour was being offered to The Cleaners from Venus. Without going into any details, I just refused point blank to do it. The way I saw it, I'd been brought to the point of illness and destitution by the music biz. Somehow I'd clawed my way back by my own endeavours and I was damned if I was going give up what I'd just made, in order to play at being rock-stars. There were meetings, there were phone calls. There was an exchange of letters. My band, were cross and disappointed with me. They really, really DID want to go and play at rock stars. Everyone was now asking me: "But what will we do? This tour could break the Cleaners over-ground." I said, "Get some other mug to do it. Fit him for the flak jacket and the thorny crown." I was doing proper work now, getting paid cash money. I was well again. I had the sun on my face. I wasn't bitter but I was angry. I'd have swung a spade at anyone who'd dared to come near me.

Eventually, I calmed down. But I still refused to do the tour. Finally, I agreed to train Dan Woods, a lovely bloke and a friend from Brighton, to do my guitar tunings and chops. Giles and Dan took a version of the Cleaners from Venus across Germany, But Nel and I didn't go. Dan Woods later told me that by the time they got to Berlin, the fans were shouting "Where's Martin?" In Germany, I was now a cautionary tale: "The Boy Who Wouldn't Eat His Lovely Fame."

This is an excerpt from The Greatest Living Englishman (2019) You can buy it off Bandcamp or from a bookshop or something if you really want it. It's good writing. Don't expect to find reviews however, because I don't send review copies to anyone. What's the fucking point?

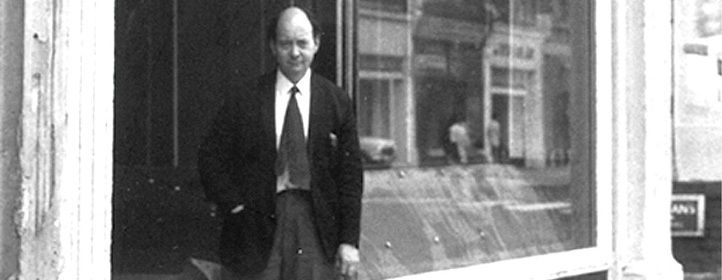

Pic: The author, after work in early winter of 1988, having become a gardener for a while in order to get his sanity back.

Comments